A case of a male with atypical anorexia nervosa and potential Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC). Names have been changed for anonymity.

Context:

Richard is receiving treatment as an out-patient for atypical Anorexia Nervosa. He had no previous psychological treatment prior to admission. He acknowledges low mood due to low weight but denies marked anxiety. Currently living alone in rented accommodation, he says he has few friends but sees his mother often. Richard’s mother prepares his meals for him and cleans his flat. Richard has had to leave his job because he was ‘too weak to work’. He is often fatigued and has a diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism which is medicated. The referring GP ruled out any link between this condition and Richard’s weight loss.

Brief History:

Richard first remembers eating irregularities in Secondary School when he noticed he was not eating as much as his peers. Aged 13, he consulted a dietician and was able to gain 1 or 2kg. Since the age of 14 he has not been able to eat very much because he feels sick when he eats. He describes this sickness as ‘a pain’ in his stomach where it ‘lurches and rejects food’. He was referred by a GP a year ago due to low body weight. He does not like his body and seeing how ‘skinny and weak’ he is. He is currently trying to gain weight but finds it difficult due to the ‘sickness’.

Current Presentation:

Richard presents as very quiet and shy with low energy and mood. He often displays blunted affect and is not able to describe emotions well. He also spoke about not being able to experience emotions early on in treatment. He is very socially isolated and can appear vulnerable in relationships, especially those he makes online. He spends most of his time online, either gaming or teaching himself how to code.

Autistic features:

Richard completed several assessments of Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) screening assessments such as the clinical interview- ADOS-2 and the self-reported AQ-10. Both of which he scored over threshold for an ASC diagnosis. More details of each assessment:

Challenges in treatment:

Richard has been seen by many different healthcare professionals, with a lack of continuity in his treatment. He has found this overwhelming in several ways including social and physical exhaustion, contributing to his persistent fatigue. Attending appointments has also been not easy, due to difficulties using public transport.

Richard is very quiet with limited insight into social norms, and clinicians working with him have often commented that it has taken as many as 5 sessions to build any level of rapport with him.

Richard’s diet is highly restricted, and he typically eats a small range of foods repeatedly until he tires of them (including milk, which is often a staple for weight restoration). His eating patterns have remained entrenched. Despite repeated attempts to please clinicians, he is not be able to achieve agreed goals.

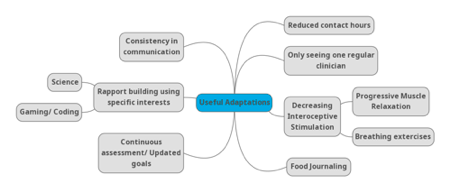

Adaptations applied in treatment:

The first adaptation for Richard’s treatment was to reduce contact hours necessary for treatment and to create some consistency in communication between the clinicians involved in his care by discussing him together in the PEACE huddles. He suggested he could only manage one visit per week and one clinician per visit, and this was organised to be with his allocated therapist. Dietician and Occupational Therapist input were reduced until they were only supporting via email. Richard reflected that he often found these emails helpful, especially when they contained clear, blunt messages.

Improving rapport became a focus during therapy sessions. Richard had previously studied pharmacology, and one clinician utilised this to improve rapport and engagement by explaining what was going on in scientific terms, with the use of diagrams. Another found that spending time talking about his specialist interests (gaming/coding) really helped with rapport, giving him the chance to ‘light up’.

Richard also benefitted from continuous assessment and formulation. As rapport building was slower than clinicians were typically used to, this process became progressive and adaptive as more information became available. As a result, treatment goals also adapted.

Food journaling allowed Richard insight into his eating patterns of being very limited in food choice and then cutting certain foods out entirely when he tired of them.

Work around promoting Richard’s interoception was very useful to him. In sessions, Richard was encouraged to pay more attention to his bodily sensations. This was done using mindfulness progressive muscle relaxation exercises, encouraging Richard to tense and really feel only one muscle at a time, breathing exercises and labelling of all internal sensations being experienced on a body diagram. The body diagram exercise was interesting for during sessions but also for homework for when Richard experienced a particularly strong emotion. This gave him the opportunity to explore and recognise what was going on internally across different scenarios.

What we learned from our experience working with Richard:

Reducing the number of clinicians involved in Richard’s care was one of the most beneficial adaptations we made, with Richard being able to focus on one social interaction a week and allowing the rapport to build. This is a very important lesson for patients presenting autistic characteristics with complicated medical profiles who may be being passed around from clinician to clinician due to other complications. We find it useful when working with the eating disorder and ASC comorbidity to reminding ourselves that “less is more” in treatment. This includes, but is not limited to, adapting the environment; the number of health professionals involved in the care; the amount of information asked in questions; and the type of conversations had (Socratic questions can sometimes over-complicate conversations).

With few changes being implemented in Richard’s treatment plan, clinicians had feelings of failure prior to the identification of his high autistic traits. Recognising for them that Richard was on the autistic spectrum clarified many things and allowed them to regain confidence in their treatment strategy, planning the sessions. Reframing the patient’s treatment in an ASC context allowed a shift in focus away from giving Richard goals to be more social and changed the focus to psychoeducation around relationships, which in turn increased Richard’s social understanding. Clinicians expectations had to be managed again, and although change was evident it was very gradual and by no means linear.

Around food intake, it was important to look at sensory issues with Richard’s ARFID-like (Avoidant/ Restrictive Food Intake Disorder) presentation. It was proposed that Richard’s eating difficulties may be to do with his interoception sensitivity (sense of feeling what is going on inside your body). Being able to discuss this with him using allowed more understanding for both parties and introduced the idea of work on bodily sensations.

Adapting our idea of assessment proved invaluable for this patient, and others to come after him. As clinicians, continuous reassessment and updating the treatment plan based on new information was essential as rapport was slowly built and more information relevant to the treatment plan was revealed.

You might find these interesting too!

This episode offers valuable reflections for clinicians, researchers, carers, and individuals with lived experience, emphasising the importance of neurodiversity-informed, person-centred care

The short website guide video is now available. he video offers a clear, step-by-step overview of how to navigate the PEACE website and explains how its design supports accessibility for different users.

In the first episode of Co-Produced, Adia and Lauren are joined by Dimitri Chubinidze to explore how inpatient eating disorder treatment is lived, felt, and made meaningful through the senses. Drawing on a year-long sensory ethnography of an adult inpatient ward, the conversation reflects on neurodivergent-affirming, co-produced research that centres lived experience. The featured study, shortlisted for the NIHR Maudsley BRC Culture, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (CEDI) Impact Award, highlights how listening attentively to bodies, senses, and experience can help shape more humane and inclusive care.