A Female with anorexia nervosa, comorbid ADHD, general anxiety disorder and suspected Autism. Names have been changed for anonymity.

Current Context:

22-year-old, female, grew up in rural community, good relationship with family when younger. Currently in college for creative arts, living in shared accommodation with other students. Comorbid anxiety and ADHD. Zainab’s ADHD was only diagnosed last year at the recommendation of her college. Previous historic low mood, suicidality and self-harm. Has reported that her self-harm is often in the context of loud noises.

Case History:

She describes herself as having been a ‘difficult child’. She struggled to read and write until she was 10 years old, and she was bullied because of this academic delay. She was exposed to difficult traumas when younger such as terminal illness of a parent and a death of a close friend. These experiences led her to start self-harming to ‘prevent’ bad things happening. Had no close friends after small friend group deteriorated.

Zainab has experienced eating difficulties since she was a child, although she has never been to a specialist eating disorder clinic before. She describes herself as quick to adopt attitudes and habits around her such as desires to attend drama school and mixing with others who strived for low weight, in turn, Zainab started to lose weight. She then attended dance school were the attitude was to be lean and strong, needing to fuel their bodies. Zainab adapted quickly to this and gained weight. She reported that this did not cause her concern.

Current Presentation:

Current episode of weight loss began after spending a significant amount of time abroad. With unfamiliar food, Zainab stopped eating and her weight began to drop. This referral was prompted by the patient who raised her own concerns with her GP around her anxiety and ‘need for control’ around food. Zainab has strongly held beliefs and rules around food, often involving numbers: “I have a thing about numbers”. Zainab understands her counting as a way of checking that she is maintaining attention in the here and now. Zainab has recently stopped taking medication for her ADHD as it was acting as an appetite suppressor. She exercises 5 times a week, not as a calorie offset but as a way of “releasing” energy, preventing restlessness and lack of concentration.

Autistic features?:

There were several indications that Zainab might benefit from being referred to the PEACE pathway. Firstly, we were aware of her self-harming in the context of loud noises. She was initially flagged up due to her response to an alarm ringing elsewhere in the building and she was asked to complete a PEACE sensory screener. This indicated that Zainab was hyper-sensitive to vision, sound and touch with sound sensitivity being a 10/10. Zainab described bright lights and loud sounds as causing an internal ‘ticking’. Touch was also rated highly, with Zainab stating that she often cannot stand the feeling of the labels in her clothes against her skin and that the only way she can manage this is when in theatre costume.

This sensitivity to touch was further highlighted when Zainab would get panic attacks during blood tests. When supported by a clinician, the panic was identified as being due to the tightness and feeling of the tourniquet and not the procedure itself. The clinician then supported Zainab in going back for a blood test, without a tourniquet, and Zainab showed no signs of distress.

Challenges faced in treatment:

Challenges for Zainab have been her sensitivity to loud noises. She would physically jump at any noise such as a door slamming. This caused challenges in treatment as in a busy environment, this was frequent, and the trail of thought was often lost. Although always cooperative and pleasant in sessions, Zainab seemed to struggle in describing her thoughts and feelings, as confirmed in the ADOS-2. This often led to complications in the session as clinicians were unsure if what they were trying to communicate was getting through to her. Further challenges were in difficulties of Zainab writing things down, as well as the difficulty in verbalisation. In terms of dietetics, she would only eat from a small range of foods, alternating between two choices for her dinners. This small range of food has been seen in other case studies in this series. This was to the extent that she reported only eating one food type over a two-year period.

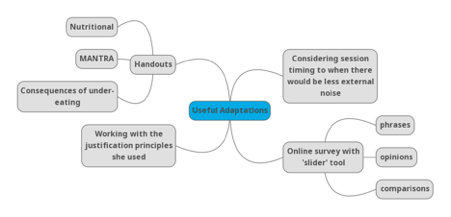

Useful adaptations applied for Zainab:

Structure was an important part of the adaptions for Zainab, with sessions being scheduled for 8am, before the clinic officially opened to ensure it was quiet. Other useful adaptations for her have been to provide extra information, such as nutritional handouts, MANTRA (Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults) handouts and often information on the consequences of undereating, which Zainab responded very well to. To address the difficulty in both verbalisation of thoughts and feelings and writing these down, Zainab’s therapist introduced an online survey questionnaire with a sliding number scale (also tailored to Zainab’s “thing” about numbers). This had a series of phrases, opinions and comparisons for Zainab to slide along to the number she identified with. Which, again, she responded well too, and this helped with rapport between client and therapist. Although Zainab refused to work on her variety of food, she was able to be supported in understanding that her body needed a fuel source at the start of the day, in order to meet the demands of the day without tiring. This led to her introducing a nutritionally balanced breakfast.

Lessons learned working with Zainab:

With patients with complex sensory profiles, it is helpful to keep these in mind and being able to explore in little more details sensory sensitivities. Zainab would have had a panic attack every time she had a blood test if her clinician had not known about her sensory atypicality and asked her directly about the tourniquet.

Another lesson learned was on the power of justification. Zainab responded well to change if it was well justified, for example, the weight gain as it made her strong and resulted in her being a better dancer. Another was the clothes labels in her drama clothes being ok as she had to wear a costume for the performance. This was similar with a bigger breakfast giving her the fuel she needed to not be tired throughout the day.

One of the most important lessons learned through Zeinab’s story was that not everyone who is eligible wants a diagnosis for different reasons. As a clinical team we all agreed that pursuing a formal diagnosis would benefit Zainab as she was in her final year of college and would be looking to move into full time employment. Zainab herself was also interested until she found out that seeking a formal diagnosis may mean that her parents have to be involved (Family interviews are often conduced in assessments such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview, to obtain as much developmental history as possible around the case). Zainab had not shared with her parents her eating disorder struggles, her new ADHD diagnosis let alone a potential autism diagnosis and she was put off initially.

You might find these interesting too!

This episode offers valuable reflections for clinicians, researchers, carers, and individuals with lived experience, emphasising the importance of neurodiversity-informed, person-centred care

The short website guide video is now available. he video offers a clear, step-by-step overview of how to navigate the PEACE website and explains how its design supports accessibility for different users.

In the first episode of Co-Produced, Adia and Lauren are joined by Dimitri Chubinidze to explore how inpatient eating disorder treatment is lived, felt, and made meaningful through the senses. Drawing on a year-long sensory ethnography of an adult inpatient ward, the conversation reflects on neurodivergent-affirming, co-produced research that centres lived experience. The featured study, shortlisted for the NIHR Maudsley BRC Culture, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (CEDI) Impact Award, highlights how listening attentively to bodies, senses, and experience can help shape more humane and inclusive care.