BAME, Eating Disorders and Autism:

Understanding and Supporting Minority Groups

We recognise that people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups with the comorbidity of autism and eating disorders face additional barriers to support along with their loved ones. Hence, our aim with this article is to build more of an understanding of the challenges faced by BAME groups and the support available.

Research on autistic people with eating disorders in BAME groups suggests that they may be faced with several additional barriers to support. These include stigmatisation within communities, isolation/denial, struggles to get a diagnosis, clinician bias, barriers to accessing support, low confidence in seeking help, language barriers and cultural differences (Beat eating disorders, 2020; Bobb, 2017; Slade, 2014; National Autistic Society, 2014: Sonneville & Lipson, 2018).

A cross-cultural research study looking at autistic traits across India, Japan and United Kingdom (Carruthers & Kinnaird et al., 2018) reported that there are potentially more similarities than differences in the presentation of autism across cultures. However, there may be subtle distinctions in how autistic traits are interpreted that influence whether or not people recognise these behaviours as relating to autism. For instance, what is considered acceptable or typical communication varies across cultures and this can influence the diagnosis of autism.

Within the eating disorder field research has also suggested that BAME groups are less likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder compared to Caucasian people (Sonneville & Lipson, 2018). Although, research has found that eating disorders may potentially be more common among BAME people than white people (Beat Eating disorders, 2020).

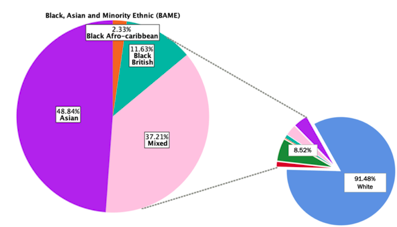

Data from our national inpatient eating disorder ward (South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust) report that 37% of our inpatients with eating disorders also have autism or high autistic traits. Concerning BAME groups and the comorbidity. Figure 1. Highlights that 91.5% of the inpatient population is white and 8.5% are from BAME groups.

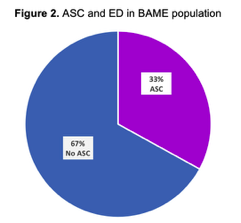

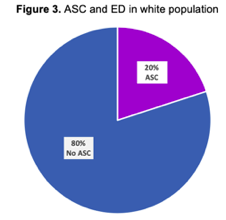

Figure 2. and Figure 3. below show that in the inpatient eating disorder service there is a 13% increase of autism or high autistic traits in the BAME population compared to the white population.

Understand and Supporting BAME groups

The literature on BAME, eating disorders and autism is limited and there is an urgent need to fund more research to develop a robust evidence base to best commission autistic people with eating disorders that meet the needs of different communities. Our current findings highlight the significance of raising awareness around the specific needs of BAME communities.

A2ndvoice is a voluntary support group run by parents and carers of autistic children and adults founded by Venessa Bobb (Branch Officer at the National Autistic Society) who is also a black mother with an autistic son (Bobb, 2017). A2ndvoice is not a BAME group, however, it is a fantastic support group who also aim to raise awareness from different perspectives outreaching to BAME groups and breaking down stigmatisation. The support group hosts regular coffee mornings and activities for parents and carers.

It is important to consider that ethnic identity can be a protective factor by the teaching of cultural values and emphasis on social themes (Wang & Fivush, 2005). However, among some BAME communities' people with the comorbidity may encounter stigmatisation due to a lack of understanding of autism and eating disorders. This can also result in denial and isolation by certain carers as they may be in denial to recognise the condition. Or feelings of blame and shame may be experienced leading to social isolation and the negligence of the available support. Therefore, it is important to increase the understanding of autism and eating disorders within communities and families by people accessing available support groups such as A2ndvoice or other online support groups available from Beat Eating disorders or the National Autistic Society (NAS). Furthermore, a charity called Hope & Compassion aims to educate BAME families in autism and other conditions or disabilities. They offer training, talks and resources in different languages. The service is also helpful in educating BAME communities to recognise autism in their loved ones and providing support to accept the diagnosis.

To tackle the underrepresentation of BAME communities which was found in in the NAS report, The way we are: autism in 2012 (Bancroft, Batten, Lambert & Madders, 2012), the latest NAS report, Diverse Perspectives report (Slade, 2014) aimed to explore the barriers that BAME communities face in accessing services with the hope to inform recommendations for decision-makers. Hence, 13 focus groups involving approximately 130 parents, siblings, carers and autistic adults were recruited to understand the needs and experiences of BAME communities.

Some of the themes that emerged from the focus group were the additional challenges faced within BAME communities. Families reported the lack of cultural competence in some professionals, which resulted in miscommunications with carers. They reported the challenges of getting a diagnosis and the delay which made it difficult to access services and funding. Also, the problems carers faced in integrating their loved one within their local community. The Diverse Perspectives report (Slade, 2014) concluded some of the following recommendations to support BAME groups: The Department of Health to support awareness of autism through faith community leaders and other champions in BAME communities and the importance of local authorities and clinical commissioning groups to consult individual families when commissioning autism services. Service providers should also ensure that information on autism is readily available in the appropriate language and promoted in BAME communities.

Furthermore, Carruthers & Kinnaird et al., (2018) found that the difficulty with diagnosing autism based on behaviours, particularly social and communicative styles, is that what is considered acceptable or typical communication varies across cultures. For example, if a child is very chatty and talkative in a culture where this is viewed as typical or encouraged (e.g. the UK), this might not stand out to parents as unusual. By contrast, for parents from cultures with a big emphasis on politeness and respect for elders (e.g. Japan), this kind of behaviour might be interpreted as a cause for concern. From the opposite perspective, a very quiet child might stand out as unusual in the UK and lead the parents to pursue an autism diagnosis, but not in Japan.

ASC is associated with a spectrum of manifestations. All autistic people share specific difficulties; however, this will affect each individual in different ways. Culture will also impact each autistic person in a different way. However, the research evidence has shown that one of the biggest challenges faced by BAME groups is services not meeting their cultural and specific needs. A2ndvoice highlights that one service provider, unfortunately, cannot support all BAME communities. The most effective way to support BAME groups is to work collaboratively by taking time to understand each person and their individual needs, then signpost to relevant organisations if need be.

Clinicians need to be aware of their own biases in supporting minority groups and being aware of their lack of cultural competence. This can be addressed through training and by working collaboratively with patients to strengthen their understanding of the patient's cultural influences and what this means for the patient and in the relationship between the two disorders. When working with families it is important to consider the way we communicate. Clinicians should be aware of the use of jargon and offering information available in other languages or making the use of interpreters. People have reported they would want information and resources that are clear, concise and accessible (Slade, 2014).

With early diagnosis of autism and eating disorders, improved awareness and commissioning, we can hopefully all work together to support BAME groups with the comorbidity to reach their full potential.

Additional information and support:

https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/

http://www.hopecompassion.org/

Support during Ramadan:

https://www.britishima.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Ramadan-Rapid-Review-Recommendations.pdf

https://people.nhs.uk/guides/covid-19-and-ramadan/

https://www.maudsleyhealth.com/blog-post/how-to-manage-your-eating-disorder-during-ramadan/

1) Bancroft, K. Batten, A. Lambert, S. & Madders, T. (2012). The way we are: autism in 2012. London: The National Autistic Society.

2) Beat Eating Disorders, (2020). New research shows eating disorder stereotypes prevent people finding help. Retrieved from https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/news/beat-news/eating-disorder-stereotypes-prevent-help

3) Bobb, V. (2017). Supporting BAME austistic peple and their families. Retrieved from https://network.autism.org.uk/knowledge/insight-opinion/supporting-bame-autistic-people-and-their-families

4) Carruthers, S., Kinnaird, E., Rudra, A., Smith, P., Allison, C., Auyeung, B., … Hoekstra, R. A. (2018). A cross-cultural study of autistic traits across India, Japan and the UK. Molecular Autism. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0235-3

5) National Auistic Society, (2014). BAME and autism. Retrieved from https://www.autism.org.uk/about/bame-autism.aspx

6) Slade, G. (2014). Diverse Perspectives Report. London, The challenges for families affected by autism from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Communites: The National Autistic Society.

7) Sonneville, K. R., & Lipson, S. K. (2018). Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students. International Journal of Eating Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22846

8) Wang, Q., & Fivush, R. (2005). Mother-child conversations of emotionally salient events: Exploring the functions of emotional reminiscing in European-American and Chinese families. Social Development. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00312.x

You might find these interesting too!

Join us online on 20 May 2026 for the PEACE Pathway Conference: Neurodiversity and Eating Disorders. The conference will explore the evolution of the PEACE Pathway toward a neurodivergent-informed service model and share insights from clinical practice, research, and co-production within eating disorder services.

Robert shares his and his wife’s experience and advice in caring for a child with autism and an eating disorder.

A neurodiversity-informed guide for patients with an eating disorder, with a focus on autism and ADHD. This resource offers practical information and strategies grounded in lived experience and clinical expertise.