Why is studying the brain important for eating disorders research?

There are two different kinds of information we can get from brain imaging research: 1) Structural information about the size and shape of the brain, and 2) Functional information about the brain’s activity.

Structural brain imaging in anorexia nervosa has demonstrated that the brain decreases in size due to malnourishment. 1 2 However, this change is reversible, and the brain tends to increase in size again upon receiving adequate nutrition during weight recovery 1. These findings give us hope that changes in the brain are not permanent, but can return to their previous state with each step towards recovery.

Studying brain function can help us to shed light on the biological processes that underlie emotion-related difficulties in people with eating disorders. While functional brain imaging can often be harder to interpret, previous work has found changes in the activity of reward-related brain regions when people with anorexia nervosa view images of body shapes and food, when compared to people without an eating disorder. 3 4

Increasingly, our research has also found differences in perceptual, decision-making, and social-emotional processes amongst adult women with anorexia nervosa, which are similar to differences commonly observed in autistic people. 5 6 7 However, we don’t know whether these changes are caused by poor nutrition, resulting in changes in brain activity only while the person is underweight (similar to the changes in brain size), or whether these changes represent autism-related differences in the brain which are present from a young age.

In order to understand this fully, it is therefore helpful to consider what we know about brain functioning in autism spectrum disorders.

Brain imaging studies have identified differences in the size and shape of some specific brain regions in autistic people; however, these differences are highly dependent on age and are less consistent than changes in brain size observed in people with anorexia nervosa. 8

Many brain studies have observed differences in the strength of communication (connectivity) between different brain regions in autistic people. Recent research has found that brain regions with increased communication in autistic people are related to memory, attention, social, and speech processes and that other areas with decreased communication are associated with speech and visual processes. 9

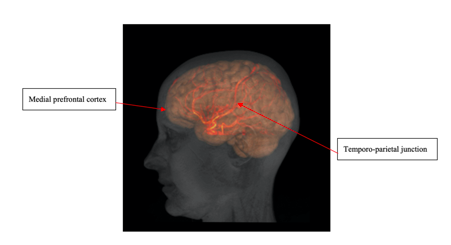

Research has also found that autistic men tend to exhibit lower levels of brain activation in brain regions including the medial prefrontal cortex and temporo-parietal junction when thinking about the perspectives of others, as compared to when neurotypical people think about the perspectives of others. 10 11 These brain regions are highlighted in Figure 1. However, these same changes are not seen in autistic women. 11

Studies have also found that autistic children and adolescents demonstrate a different pattern of brain activity when performing tasks that involve detail-focused visual searches. 12 13 This may be related to the fact that autistic people tend to be better than neurotypical people at detail-focused tasks, but have more difficulties with tasks that require them to consider the “bigger picture”. 14

3. What have we learned from our current brain imaging studies?

As mentioned above, researchers didn’t know whether autistic traits seen in adult women with anorexia nervosa are caused by poor nutrition, or whether these changes represent autism-related differences in the brain which are present from a young age.

One way to investigate this question would be to examine the brains of a whole age cohort of children and subsequently see if changes in brain structure and function in childhood predict who will go on to develop anorexia nervosa. However, brain imaging is very expensive and it is, therefore, difficult to fund research on so many people. Additionally, it can be hard to keep in contact with such a large group of participants over many years.

Therefore, another way to investigate our research question is to investigate the brain structure and function of young people with anorexia nervosa, who have not had the disorder for a very long time. This approach allows us to see whether differences in the brain can be seen very early on the disorder, or only emerge after a more chronic course of illness (seen in older adults with anorexia nervosa).

Early studies with small samples suggested that both adolescent and adult women with anorexia nervosa exhibit different patterns of brain activity when taking the perspectives of others, when compared to participants without an eating disorder. 15 16 However, our much larger study of young women with anorexia nervosa has not repeated these findings. Instead, our findings are similar to those seen in autistic women, who also do not exhibit differences in brain activity when taking the perspectives of others. 11

We also investigated whether young women exhibit a different pattern of brain activity when completing a detail-focused visual search task, as compared to young women without an eating disorder. This study did not find differences between participants with anorexia nervosa and controls; however, there were some differences between participants with anorexia nervosa and participants weight-recovered from anorexia nervosa. This difference may reflect compensatory mechanisms developed through recovery, although more research is needed to know for sure.

We also found that the degree of brain activity in visual processing regions whilst performing a visual search task was associated with autistic traits. This finding suggests that the relationship between autism and brain markers exists even at a trait level in populations without a diagnosed autism spectrum condition.

We also know that many individuals with eating disorders have difficulties with emotions, 17 so we investigated what happens in the brain during a task involving emotional faces. We found that young women with anorexia nervosa had increased connectivity to frontal brain regions, but that young women weight-recovered from anorexia nervosa do not exhibit differences when compared to participants without an eating disorder. Differences in connectivity to frontal brain regions have also been shown in autistic people and may be a biological marker of emotional difficulties across a range of psychiatric conditions. 18 We also found that weight-restored individuals have different levels of activity in brain regions called the frontal lobe and temporal lobe when viewing emotional faces, when compared with individuals without anorexia nervosa. The location of the temporal lobe can be seen in Figure 2.

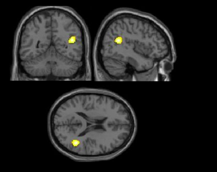

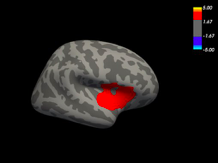

When we looked at the structure of the brain we found that early in the course of anorexia nervosa, the whole brain is not smaller compared with people who do not have anorexia nervosa. Our results suggest that how long someone is unwell with anorexia nervosa is important for brain size, although these changes can still reverse with weight recovery. We also found that a key area of the brain associated with emotion, the amygdala, is smaller and that the temporal lobe is thinner and less folded in young women with anorexia nervosa, but weight restoration reverses these changes. The area of the temporal lobe associated with structural differences is illustrated in Figure 3. On the whole, these structural findings, therefore, continue to support previous literature demonstrating that changes in the size and shape of the brain during periods of malnourishment are not permanent. Rather, these findings give us greater hope for the potential of each person with an eating disorder to achieve a full recovery.

1) Seitz, J., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., & Konrad, K. (2016). Brain morphological changes in adolescent and adult patients with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Neural Transmission, 123(8), 949-959.

2) Fonville, L., Giampietro, V., Williams, S. C. R., Simmons, A., & Tchanturia, K. (2014). Alterations in brain structure in adults with anorexia nervosa and the impact of illness duration. Psychological Medicine, 44(9), 1965-1975.

3) Fladung, A. K., Grön, G., Grammer, K., Herrnberger, B., Schilly, E., Grasteit, S., ... & von Wietersheim, J. (2010). A neural signature of anorexia nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(2), 206-212.

4) Cowdrey, F. A., Park, R. J., Harmer, C. J., & McCabe, C. (2011). Increased neural processing of rewarding and aversive food stimuli in recovered anorexia nervosa. Biological psychiatry, 70(8), 736-743.

5) Lang, K., Lopez, C., Stahl, D., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2014). Central coherence in eating disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 15(8), 586-598.

6) Leppanen, J., Sedgewick, F., Treasure, J., & Tchanturia, K. (2018). Differences in the Theory of Mind profiles of patients with anorexia nervosa and individuals on the autism spectrum: a meta-analytic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 90, 146-163.

7) Roberts, M. E., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. L. (2010). Exploring the neurocognitive signature of poor set-shifting in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(14), 964-970.

8) Pua, E. P. K., Bowden, S. C., & Seal, M. L. (2017). Autism spectrum disorders: Neuroimaging findings from systematic reviews. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 34, 28-33.

9) Snyder, W., & Troiani, V. (2020). Behavioural profiling of autism connectivity abnormalities. BJPsych Open, 6(1).

10) Castelli, F., Frith, C., Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2002). Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain, 125(8), 1839-1849.

11) Kirkovski, M., Enticott, P. G., Hughes, M. E., Rossell, S. L., & Fitzgerald, P. B. (2016). Atypical neural activity in males but not females with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(3), 954-963.

12) Manjaly, Z. M., Bruning, N., Neufang, S., Stephan, K. E., Brieber, S., Marshall, J. C., ... & Fink, G. R. (2007). Neurophysiological correlates of relatively enhanced local visual search in autistic adolescents. Neuroimage, 35(1), 283-291.

13) Ring, H. A., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Williams, S. C., Brammer, M., Andrew, C., & Bullmore, E. T. (1999). Cerebral correlates of preserved cognitive skills in autism: a functional MRI study of embedded figures task performance. Brain, 122(7), 1305-1315.

14) olliffe, T., & Baron‐Cohen, S. (1997). Are people with autism and Asperger syndrome faster than normal on the Embedded Figures Test?. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 527-534.

15) McAdams, C. J., & Krawczyk, D. C. (2011). Impaired neural processing of social attribution in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 194(1), 54-63.

16) Schulte-Rüther, M., Mainz, V., Fink, G. R., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., & Konrad, K. (2012). Theory of mind and the brain in anorexia nervosa: relation to treatment outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(8), 832-841. e811.

17) Harrison, A., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2010). Attentional bias, emotion recognition, and emotion regulation in anorexia: state or trait?. Biological psychiatry, 68(8), 755-761.

18) Swartz, J. R., Wiggins, J. L., Carrasco, M., Lord, C., & Monk, C. S. (2013). Amygdala habituation and prefrontal functional connectivity in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(1), 84-93.

You might find these interesting too!

The short website guide video is now available. he video offers a clear, step-by-step overview of how to navigate the PEACE website and explains how its design supports accessibility for different users.

In the first episode of Co-Produced, Adia and Lauren are joined by Dimitri Chubinidze to explore how inpatient eating disorder treatment is lived, felt, and made meaningful through the senses. Drawing on a year-long sensory ethnography of an adult inpatient ward, the conversation reflects on neurodivergent-affirming, co-produced research that centres lived experience. The featured study, shortlisted for the NIHR Maudsley BRC Culture, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (CEDI) Impact Award, highlights how listening attentively to bodies, senses, and experience can help shape more humane and inclusive care.

This blog by Lauren Makin shares insights from recent research on how eating disorder support can better meet the needs of Autistic and ADHD adults. It highlights the importance of recognising neurodivergence and adapting care to sensory, communication, and routine needs, based on what people with lived experience say is most helpful.